Store Front Museum

Store Front Museum

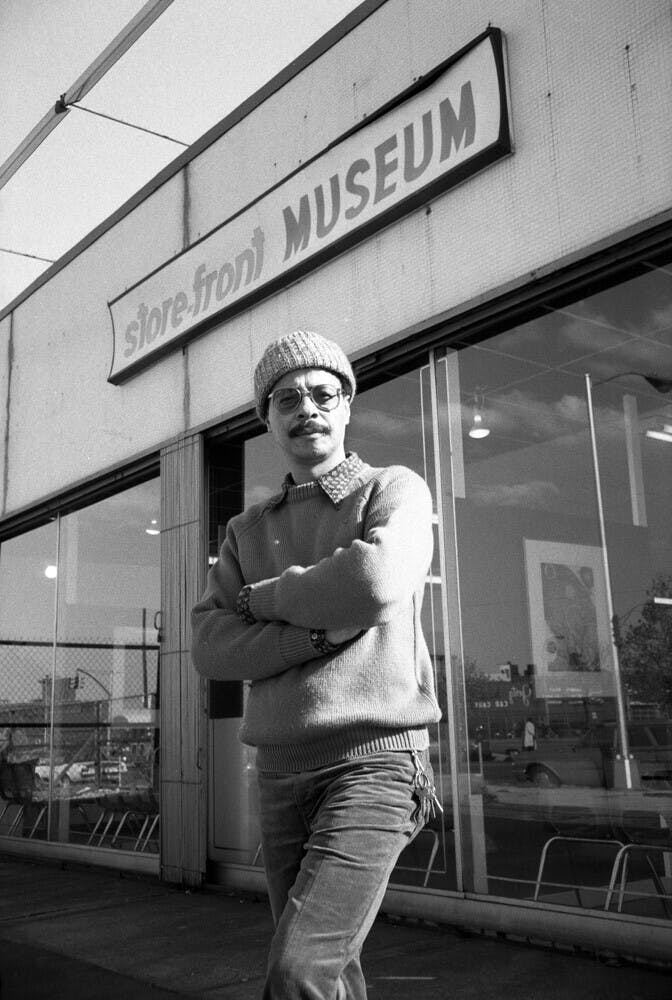

“We have to bring art to the Black communities ... It’s important for Black people to have this identity. They have to feel this pride. It’s our responsibility to bring it to them.” — Tom Lloyd, 1969

“I can’t imagine an artist—a Black artist—functioning without knowing he’s Black, without being concerned about what’s happening to us, without being concerned about our very lives. We’re Black. No matter what kind of work you do, you’re influenced by all these things.” — Tom Lloyd, quoted in Romare Bearden et al., “The Black Artist in America: A Symposium,” Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 27, no. 5 (January 1969)

While Tom Lloyd gained recognition for his striking electronic light-based artworks, the artist, educator, and activist was also a steadfast advocate for community engagement in the arts.

Lloyd played an active role in the formation of the Art Workers’ Coalition, a collection of artists, filmmakers, writers, critics, and museum staff who fought for political and economic reforms within New York City’s major art institutions, pressuring them to adopt more inclusive practices within exhibitions, collecting, and admissions policies. Lloyd aimed to redress the underrepresentation of Black artists in cultural institutions, but he also stressed the importance of cultivating Black audiences—and he knew precisely where these two convictions could converge. In 1971 he transformed an abandoned Goodyear dealership in South Jamaica, Queens, into the Store Front Museum—the first art museum in the borough.

A native of Jamaica, Queens, Lloyd recognized the urgent need for a cultural institution that directly served the local Black community.

The Store Front Museum operated for sixteen years, offering a wide range of exhibitions, performances, and public programs focused on Black art and culture, with activities such as karate classes, annual festivals, exercise programs, and other events that promoted cultural pride and collective empowerment. After a long struggle and an inability to find a new property, the museum was forced to close its doors in 1988.

While Tom Lloyd gained recognition for his striking electronic light-based artworks, the artist, educator, and activist was also a steadfast advocate for community engagement in the arts.

Lloyd played an active role in the formation of the Art Workers’ Coalition, a collection of artists, filmmakers, writers, critics, and museum staff who fought for political and economic reforms within New York City’s major art institutions, pressuring them to adopt more inclusive practices within exhibitions, collecting, and admissions policies. Lloyd aimed to redress the underrepresentation of Black artists in cultural institutions, but he also stressed the importance of cultivating Black audiences—and he knew precisely where these two convictions could converge. In 1971 he transformed an abandoned Goodyear dealership in South Jamaica, Queens, into the Store Front Museum—the first art museum in the borough.

“We have to bring art to the Black communities ... It’s important for Black people to have this identity. They have to feel this pride. It’s our responsibility to bring it to them.” — Tom Lloyd, 1969

“I can’t imagine an artist—a Black artist—functioning without knowing he’s Black, without being concerned about what’s happening to us, without being concerned about our very lives. We’re Black. No matter what kind of work you do, you’re influenced by all these things.” — Tom Lloyd, quoted in Romare Bearden et al., “The Black Artist in America: A Symposium,” Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 27, no. 5 (January 1969)

A native of Jamaica, Queens, Lloyd recognized the urgent need for a cultural institution that directly served the local Black community.

The Store Front Museum operated for sixteen years, offering a wide range of exhibitions, performances, and public programs focused on Black art and culture, with activities such as karate classes, annual festivals, exercise programs, and other events that promoted cultural pride and collective empowerment. After a long struggle and an inability to find a new property, the museum was forced to close its doors in 1988.

Lloyd’s contributions remain underexamined in art historical narratives—yet his work offers a crucial lens through which to reconsider the intersections of race, space, and institutional power.

Lloyd’s contributions remain underexamined in art historical narratives—yet his work offers a crucial lens through which to reconsider the intersections of race, space, and institutional power.